Why They're All Black

We tiptoe around race and crime. Let's stomp a bit, as long as racists are underfoot.

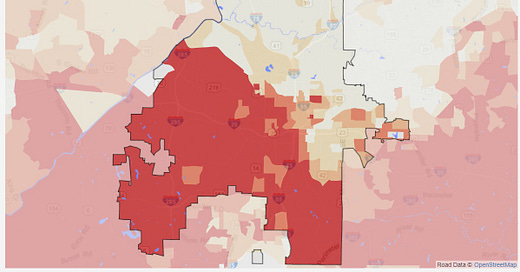

I’m chewing on the 2021 homicide statistics in Atlanta. As I’ve mentioned before, I think the current wave of violent crime peaked in early October after things took off in May 2020. Atlanta sustained 158 murders in 2021, one more than the previous year and 59 more than 2019.

Some of the top-line statistics provide real insight into what’s been driving c…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Atlanta Objective with George Chidi to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.