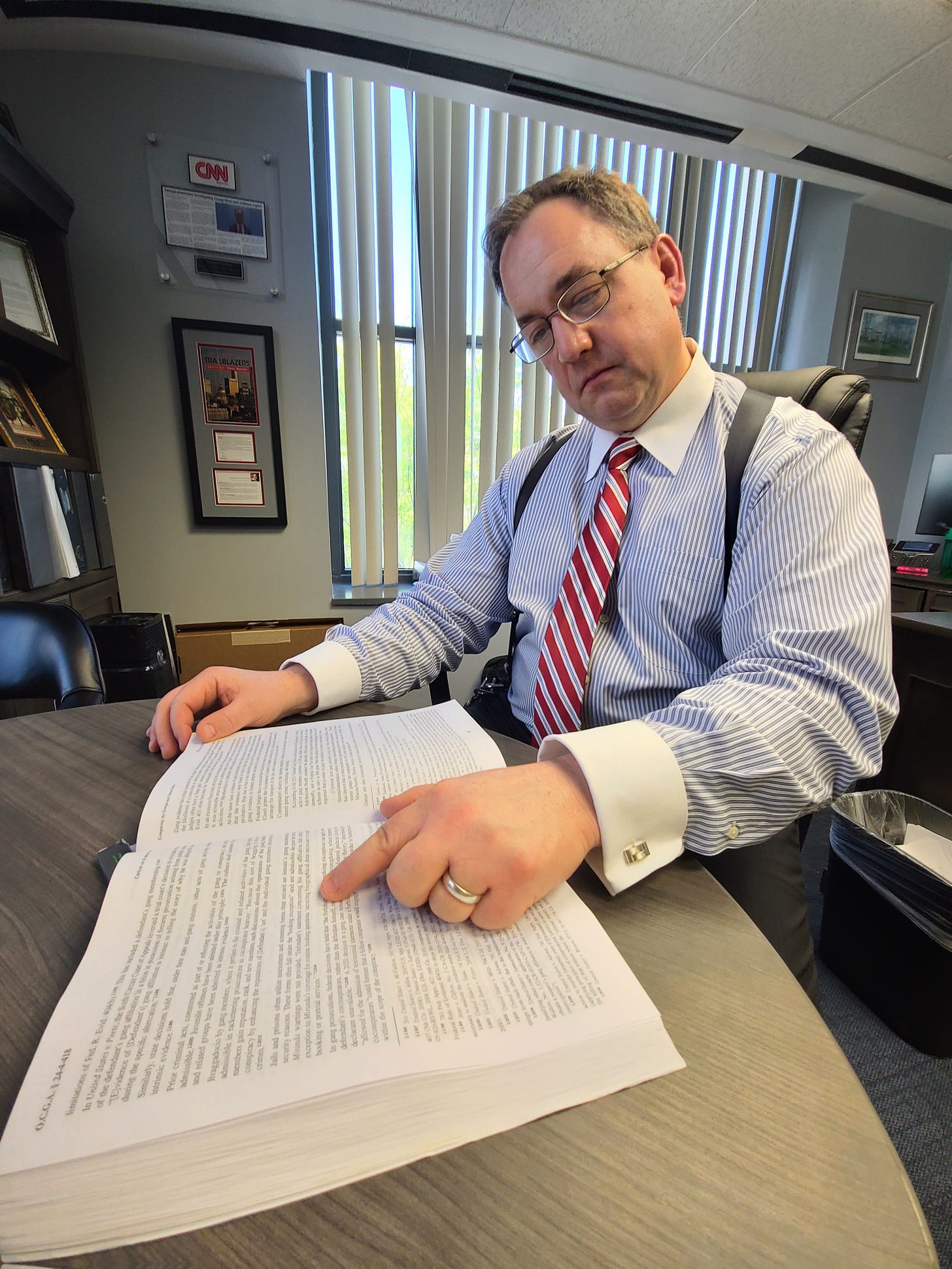

Michael Carlson: Gangs On Trial

Michael Carlson, Fulton County's gang prosecutor, literally wrote the book on Georgia's gang law. Here's how he will apply it in Atlanta.

When Fulton County’s district attorney Fani Willis came to office 16 months ago, she started hiring prosecutors to start clearing the county’s notorious case backlog. The office had been bleeding talent. Evidently, the despair of the dysfunction made it less attractive, even though prosecuting crime in the state capitol should have been a major career b…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Atlanta Objective with George Chidi to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.