"Don't Take Me With You."

The "snitching" conversation is toxic. I don't care for it. If you care about rap and prefer to see fewer people die, neither should you.

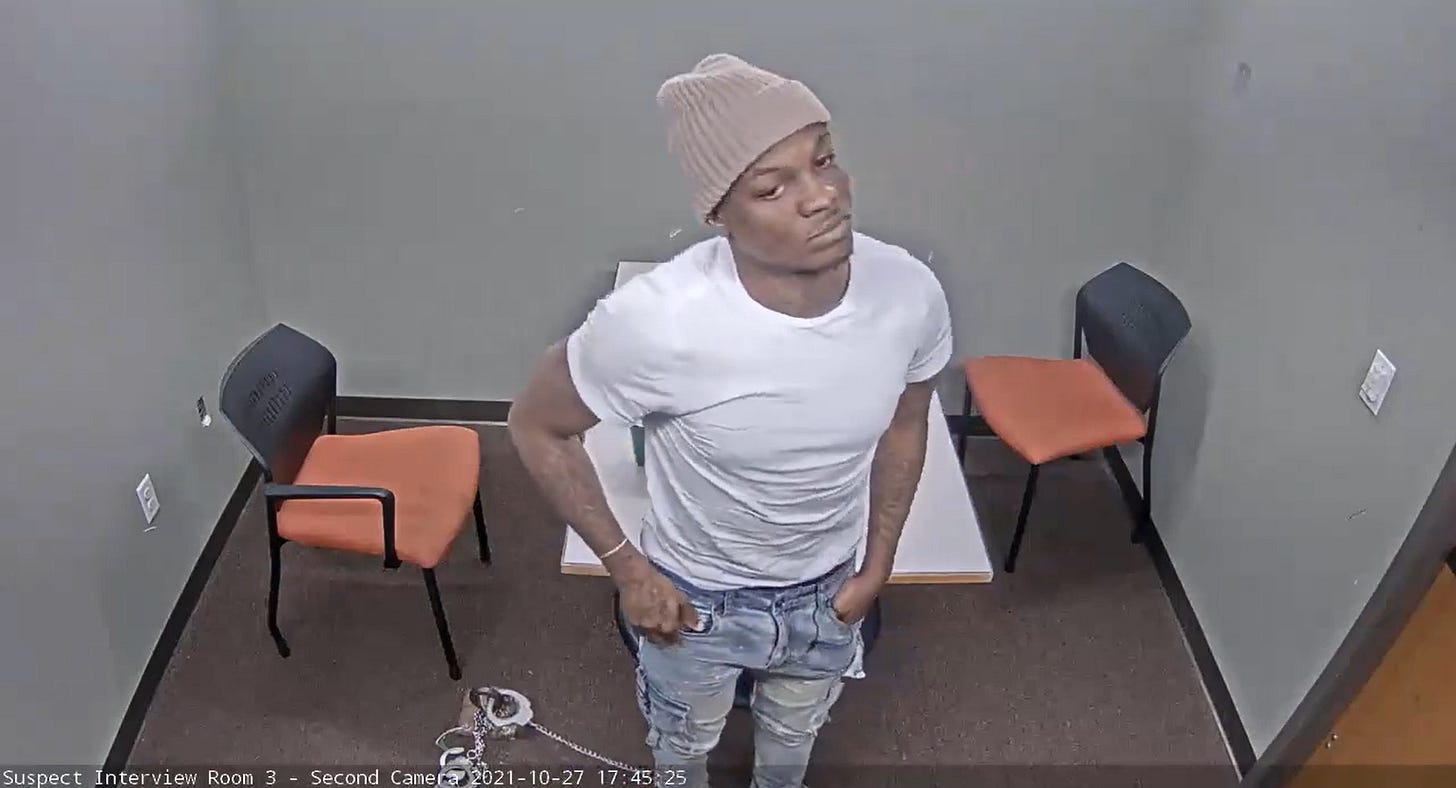

A video has begun to circulate of Kenneth Copeland, “Lil Woody” of YSL fame, being interrogated after his arrest in October 2021 on weapons charges. Copeland is speaking to Fulton County investigators, apparently discussing a planned hit on one of his “ops.”

The full video — at least until Judge Ural Glanville decides to go after it — is more than three …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Atlanta Objective with George Chidi to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.