A Night On Edgewood Avenue

One sixteen-hour view of the hottest street in Atlanta, a year after its most dangerous day.

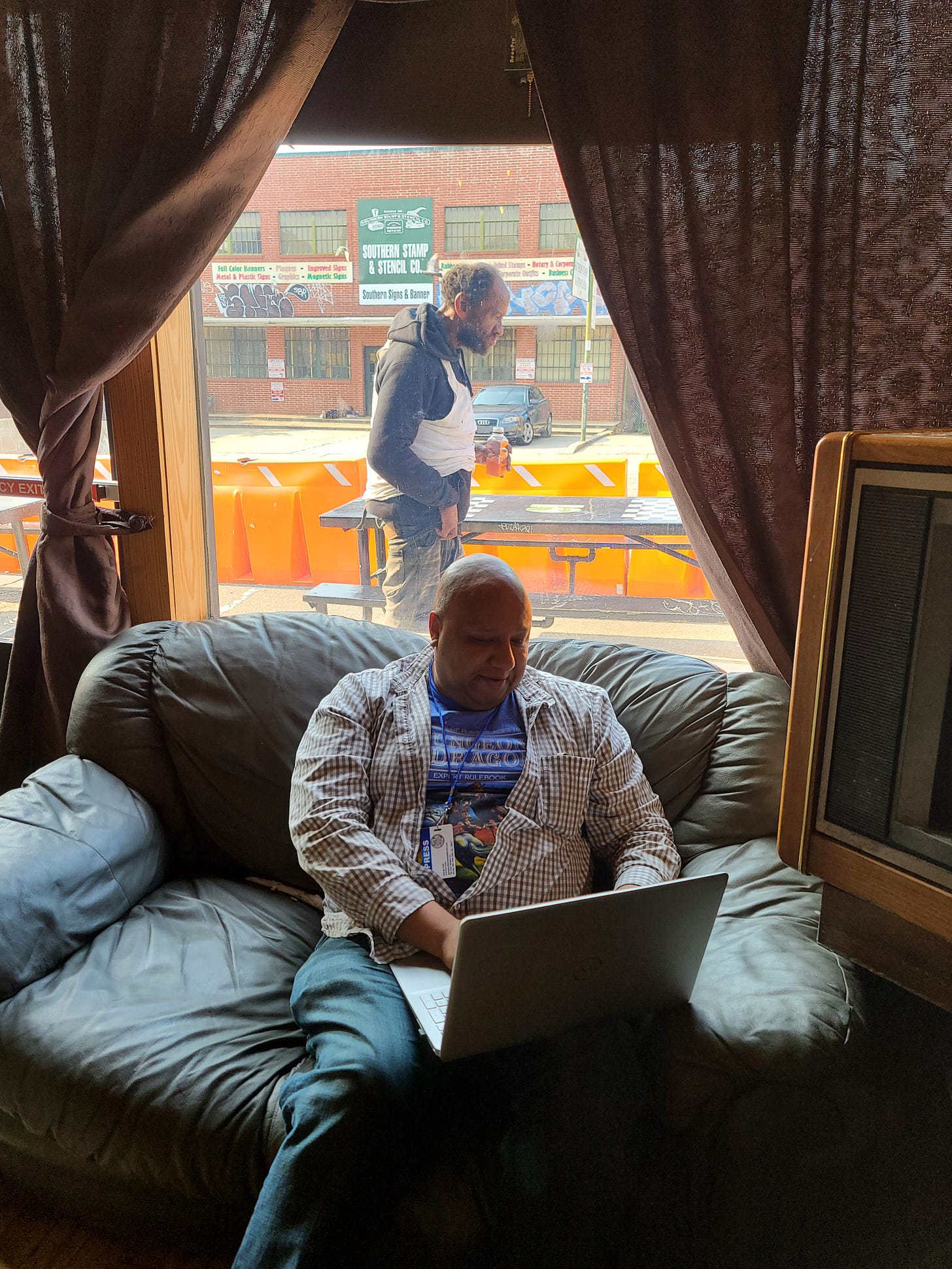

It’s 6 p.m. on July 3, and I’m at Joystick, my happy place.

For the next 10 hours or so, I’m going to be chronicling the madness I am sure will unfold on Edgewood Avenue tonight — madness that is already upon us. For this is Independence Day weekend, and the Hawks are in the finals. People have already started pouring into the bars and nightclubs, lightl…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Atlanta Objective with George Chidi to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.